This blog, the second in an occasional series written by Digitunity’s Health Advisor, Amy Sheon, highlights opportunities for disseminating digital inclusion-related resources through healthcare. To read the earlier blog, click the linked text: Post #1 The next blog in the series will tackle how to leverage Healthcare for Digital Inclusion.

The COVID-19 pandemic strikingly revealed the fundamental importance of internet connectivity and digital skills for health. First, having devices, connectivity, and digital skills are essential for using telehealth, which abruptly became the main healthcare delivery mode during the shutdown. Second, internet-accessed patient portals became a key method for scheduling vaccine appointments.

Portal use disparities have been abundantly clear for a decade, and telehealth disparities became apparent early into the pandemic. Thus, the dramatic disparities in vaccine uptake for poor and minority Americans, and lower telehealth use among those groups and among seniors, as well, were entirely predictable due to well characterized lower rates of internet adoption among these groups.

Education and employment are strong social determinants of health. Therefore, digital gaps also have an indirect effect on health, given the digital requirements for online schooling and employment during the pandemic. Due to these factors, those leading digitally impoverished lives have borne an overwhelming excess burden of the pandemic.

Nevertheless, a pandemic bright spot is the change from decrying the need to close the digital divide to actually devoting resources to doing so. The Emergency Broadband Benefit (EBB) has made available discounts of up to $50 per month toward broadband service and $100 for purchase of a laptop, desktop computer, or tablet devices for families with financial or pandemic-related needs.

Two federal programs, the COVID-19 Telehealth Program, and the Connected Care Pilot Program, provided $200 million and $100 million, respectively, for health systems to purchase devices and connectivity that would enable people to manage their health. Collectively, these programs offer unprecedented opportunities for health systems to help patients get connected to the internet.

However, neither the EBB nor the COVID-19 Telehealth Program cover the cost of outreach, helping people actually sign up for the service, get training to use devices, or ongoing technical support beyond warranty periods. The Digital Equity Act, incorporated into the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (the “Infrastructure Bill”), will rectify that shortcoming by funding community-based digital inclusion activities.

While optimal methods of helping people connect to the internet are yet to be identified, a number of communities are pilot testing the use of digital navigators to provide one-on-one support for getting connected. Yet, health systems are just beginning to consider how to get people connected and trained.

Why Healthcare is Positioned to Address Digital Poverty

Comprising over 17% of the U.S. GDP, healthcare has significant resources, opportunities and motivations for addressing the healthcare digital divide. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HI-TECH) Act of 2009 provided over $25 billion to encourage health systems to adopt electronic health records, including incentives that now enable virtually all patients free online portals to their electronic health records—if they have a device, a secure internet connection, and the necessary digital skills.

Secondly, the Affordable Care Act incentivized providers to reduce patients’ need for care, leading many to encourage patients to actively manage their health using methods such as patient portals and remote monitoring, as described in the last blog. Digital health technologies such as connected devices, wearables and apps were first embraced by digital literati who were already engaged with their health.

While wearables and smartphone apps have since become ubiquitous, elderly and poor people are less likely to use them for economic and digital literacy reasons. Some health systems that were already focused on disadvantaged patients have long sought to address digital poverty as a barrier to digital health technology use, but most lacked the resources to address these gaps.heal

Other health systems showed little interest in digital engagement with vulnerable patients until the pandemic came along. With many now clamoring for ways to connect with their more vulnerable patients, six measures are offered below to ensure that digital health tools, e.g. telehealth, remote monitors and portals, are available to those who stand to benefit the most from them.

How Healthcare Can Address Digital Poverty

1. Monitor Equitable Digital Engagement

Health systems should monitor disparities in patients’ use of digital health tools. Differences in audio versus video telehealth visits should be examined because audio visits may indicate lack of digital connectedness or skills. Meaningful portal use should also be examined. The frequency of portal use and use of multiple functions should be considered, along with messaging and functions that make healthcare more convenient, such as online scheduling and bill paying.

Most health systems capture the patient’s age, race, ethnicity, address, and source of payment for health care in their electronic health records. Some also document the patient’s preferred language and health literacy. Health systems should use this information to compare digital health tool use for patient groups that differ in these ways. Looking at use geographically is especially important because clusters of low use may reveal areas where affordable broadband service is unavailable or device access is limited.

2. Screen Patients to Identify Digital Gaps

Health systems should screen all patients, or those not using digital tools to determine whether they have a computer that could be used for a video call, a secure, reliable broadband connection, and the skills needed to use the desired tool. A “low bar” should be used to identify people who are not “telehealth ready.”

Many people will say they have a device that could be used for telehealth, but may be thinking of an audio-only visit, or only have intermittent access to a borrowed device. Similarly, people may say they have access to the internet, but that access may not be in a setting appropriate for a telehealth visit or daily use of a remote telemedicine monitor.

For people who have devices and connectivity, it may be useful to ask about specific digital skills that may be required for telehealth such as using email and patient portals, downloading apps, adjusting cameras and mic settings.

3. Refer Patients to Close Digital Gaps

Before implementing digital health readiness screening, health systems should have a workflow designated for addressing digital equipment, connectivity, or basic skill gaps revealed during screening. They could arrange, for example, to refer patients to local and national organizations that comprise a “digital inclusion ecosystem” to close device and skill gaps.

For more information on organizations working to address digital inclusion, contact Digitunity.

We know from a careful study in California that merely providing people with discount internet offers does not lead to adoption, due to, among other reasons, the obvious barriers that people without the internet face in uploading documentation needed to initiate service.

Digital navigators have been proposed as a solution. They are usually trusted members of the community hired by health systems or community organizations who are knowledgeable about connectivity, device and training options, and walk people through getting connected and getting new equipment up and running.

4. Digital Health Coaching

Many patients who are generally “telehealth ready” would nevertheless welcome and benefit from assistance using digital health tools. People with good digital skills could be directed to a video or online instructions, but a hands-on approach is often needed for digital novices. Nevertheless, even people with strong digital skills frequently encounter problems launching telehealth visits, many of which reflect basic or advanced skill gaps.

Common technical issues facing new telehealth users include:

- Using a specific browser or browser version.

- Adjusting security settings for the device, browser, or internet.

- Adjusting camera, microphone, or speaker settings.

- Downloading an app.

Some health systems offer, and many patients welcome, a practice visit to work out such kinks. This is where a digital health coach comes in. This individual might be a member of the clinical team or based in a community setting, such as a library, where they complement the skills of staff generically trained to help visitors use an array of digital applications but lack specific knowledge of health applications. Digital health coaches can be trained to patiently help people with technology issues and also to explain when and why the technology should be used.

They might also address privacy concerns and provide tips on lighting and camera placement. Community health workers, who understand the lived experiences of vulnerable people, are well-suited to be trained either as digital navigators, as digital health coaches, or both. While both positions require knowing how to teach digital skills, navigators specialize in helping people get connected and online, often for the first time, while coaches are trained to teach people to use specific health applications.

5. Tech Support

Even some well-prepared patients encounter glitches when trying to join a telehealth appointment or use a device at home. Some healthcare organizations may use their IT staff to provide technical support to providers and patients having telehealth visits. Others may use the tech support line offered by the technology provider. The in-house service must be familiar with technology that they didn’t develop.

Whereas the outsourced service should understand how the service works at the caller’s institution. Either way, it’s likely that a majority of the calls will concern basic device connectivity issues tech support people may consider “not my problem.” To address telehealth access disparities, it’s essential that health systems be prepared to address issues related to devices, connectivity and skills, even for people thought to be telehealth ready.

In addition to the navigator and coaching solutions described above, systems might consider contracting with a refurbisher already providing technical support to recipients of donated devices in their local community. It might be easier for a health system to teach the refurbisher’s tech support team to help patients access telehealth, than to train a telehealth support team to address patients’ issues with devices and the internet.

6. Optimize Technology

A final strategy geared toward improving digital access in healthcare is to ensure that digital health technologies have been optimized for use by people with lower levels of digital skills, with lower end or older devices, and with slow internet or data caps. The best time to address this is before signing a vendor contract. Consideration should also be given to planning how such products will be rolled out to patients.

One promising strategy is for a health system to identify and groom patients who are either recent internet adopters or face other types of barriers mentioned above to work with the vendors to improve products. Compensation should be offered by the health system or the vendor for the time patients spend getting trained and offering feedback. An excellent model for this is the Savvy Coop, a member-owned group that enables patients to get paid for giving input to companies developing therapeutics and health technologies.

Conclusion

Digital health tools could be especially valuable to people with chronic illnesses who face logistical barriers to in person care, such as transportation, childcare, time off of work, etc. Since such individuals are the most likely to be unready for digital health technology, health systems should monitor disparities in digital engagement, and identify patients who need and want assistance getting equipped, connected, and trained in basic digital skills.

Such individuals should be referred to community organizations where they can get assistance from Digital Navigators. The next blog in this series will highlight referral strategies and opportunities. Health systems should then train digital health coaches to help patients understand why and how to use the technology, and in the specific digital skills needed for particular applications.

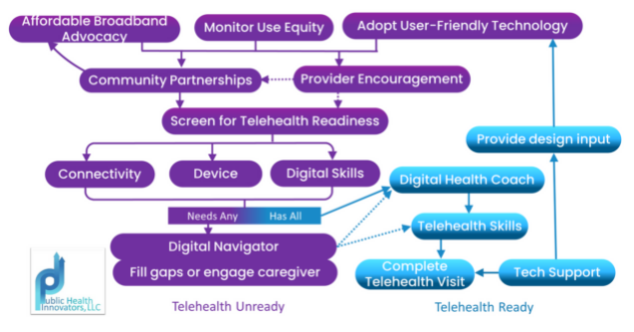

Tech support must also be available for people who have difficulty in real time, with resources in place to help with device, connectivity and internet navigation issues that may arise. Collectively, these steps comprise much of the Digital Inclusion Model for Telehealth Equity developed by Public Health Innovators, shown in the Figure below

About the Author

About the Author

Amy Sheon has over 30 years of experience working on emerging public health challenges and cutting-edge solutions. She recently served as a Senior Fellow at the National Digital Inclusion Alliance, and is the Research Director for the Telehealth Equity Coalition.

Through her consulting firm, Public Health Innovators, LLC, she provides digital health equity consultations to leading health systems, non-profit, academic, and government organizations. Her most recent publication is “Digital Inclusion as a Social Determinant of Health.”